I remember the moment a consultant told me I was “in remission”. It sounded like winning a small but respectable prize. A handshake. A certificate. Perhaps a short parade. Instead, I walked home exhausted, in pain, and quietly calculating how far I could get before I needed a toilet.

This is the quiet problem with Crohn’s symptoms in remission. On paper, things look tidy. In real life, the body carries on like it missed the meeting.

If that disconnect feels familiar, you are not alone. And more importantly, you are not imagining it.

This article shares information and lived experience. It does not offer medical advice. Always speak to your IBD team or GP about symptoms, tests, or treatment decisions.

Remission does not mean symptom free

In medical terms, remission usually means inflammation is under control. Blood markers behave. Scans look polite. Calprotectin stops shouting.

But Crohn’s symptoms in remission often tell a different story.

Fatigue lingers. Pain nags. Urgency turns daily planning into a logistics exercise. Accidents happen. Social life shrinks. Work takes more effort than it should.

None of this contradicts remission. It simply sits alongside it.

The mistake we make is assuming that the absence of inflammation guarantees the presence of wellbeing. Biology is rarely that cooperative.

The symptoms people struggle with most

When researchers finally asked people with inflammatory bowel disease what bothered them most, the answers were not subtle.

The IBD-BOOST programme surveyed 8,486 people across the UK. The results were stark, if you live with this condition.

- Over half reported bowel incontinence in the previous week

- Around one in three reported fatigue

- Around one in five reported ongoing pain

- Nearly one in three wanted help for all three symptoms

These were not fringe complaints. They were mainstream experiences.

The study also found that symptoms tend to arrive in packs. Fatigue rarely travels alone. Pain and urgency reinforce each other. Quality of life drops fastest when more than one symptom sets up camp.

That matters, because most advice still treats symptoms as isolated faults rather than a system under strain.

Why Crohn’s symptoms persist in remission

Here is the counterintuitive bit.

The symptoms that dominate daily life are often not driven directly by inflammation. They are shaped by a mix of nerve sensitivity, muscle function, sleep disruption, stress responses, learned avoidance, and the simple wear and tear of living on alert.

Pain can linger after inflammation settles. Fatigue can outlast disease activity by months or years. Urgency can become a habit the gut struggles to unlearn.

The body is a cautious bureaucrat. Once it has learned that danger might appear without warning, it keeps the alarms wired in.

This is not a failure of treatment. It is a survival strategy that has overstayed its welcome.

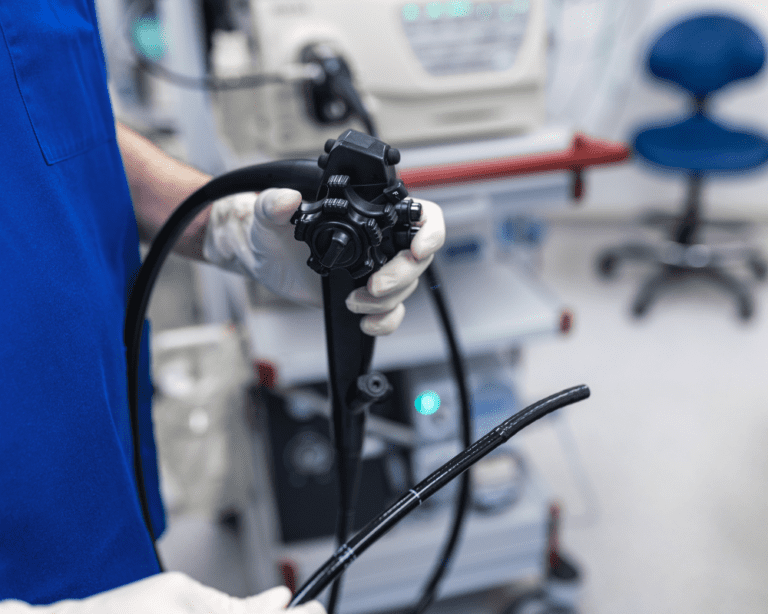

Why help feels hard to access

One uncomfortable truth from the IBD-BOOST research is that people often feel these symptoms are not taken seriously. That does not mean clinicians do not care. It means the system is optimised for something else.

Clinics are built to control inflammation. Appointments are short. Nurses are stretched. Fatigue, pain and urgency take time to unpack, and time is the one resource in shortest supply.

IBD nurses involved in the research were clear. They wanted to help. They simply lacked the capacity to do so at scale.

This gap between need and structure explains a great deal of frustration on both sides of the consultation desk.

What the IBD-BOOST research actually tested

IBD-BOOST was not a single experiment. It was a long, careful programme that tried to tackle the problem from several angles.

First, researchers listened. Interviews and focus groups confirmed what many people already knew. Living with fatigue, pain and urgency reshapes work, relationships, and confidence.

Second, they measured the scale of the issue through the national survey.

Third, they built practical tools.

One was a structured checklist and flowchart, known as Optimise, to help nurses screen for reversible contributors to symptoms.

Another was a 12-session online self-management programme, supported by a facilitator, aimed at helping people manage symptoms at home.

Both were grounded in real needs. Neither promised miracles.

What the Optimise checklist revealed

The Optimise tool produced one of the most quietly interesting findings in the whole programme.

In 43 percent of participants, the checklist indicated a test or intervention that might improve symptoms. Some had red flags that needed follow-up. Others had treatable contributors that had not been fully explored.

Importantly, nurses found the checklist feasible and easy to use.

This matters because it shows that some symptom burden sits in the gaps between appointments rather than in the disease itself. Asking better questions can surface useful action.

That does not solve everything. But it does solve something.

What the self-management trial found and did not find

Here is where honesty matters.

The randomised trial of the online programme did not show a significant improvement in disease-specific quality of life, fatigue, or pain compared with usual care.

That result needs to be said plainly.

There were small improvements in bowel incontinence and general health-related quality of life. Economic analysis suggested the approach could still be cost-effective. People who completed more sessions tended to do better.

But overall, the researchers concluded they could not say the programme was helpful in its current format.

That is not failure. It is information.

Why engagement is the real constraint

Only 57 percent of participants completed the minimum number of sessions planned. The average completion was five out of twelve.

It is tempting to call this a motivation problem. The study did not.

When fatigue, pain and urgency fluctuate, structured programmes compete with survival tasks. On bad days, logging in is not a priority. On good days, you want to enjoy them.

The people who engaged most benefited most. That suggests the issue is not effort or interest. It is fit.

Self-management support must bend around life with Crohn’s, not the other way round.

What this means if you live with Crohn’s symptoms in remission

There are a few grounded conclusions worth taking seriously.

- Persistent symptoms are common, even in remission

- Wanting help for fatigue, pain or urgency is reasonable

- Some symptoms may have modifiable contributors worth checking

- Lack of improvement is not a personal failure

- Small gains still matter when symptoms stack up

The research does not offer a silver bullet. It does offer validation.

Your experience sits squarely within what thousands of others report.

What needs to change next

The IBD-BOOST team are not retreating. They are adapting. Future work will focus on formats that fit real lives better, including app-based approaches and improved engagement design.

More broadly, care needs to recognise that inflammation control is necessary but not sufficient. Symptoms deserve attention in their own right.

Better questions. Better timing. Better expectations.

None of this is dramatic. That is precisely why it might work.

Common questions about Crohn’s symptoms in remission

Yes. Fatigue, pain and urgency can persist even when inflammation is controlled. Remission reflects disease activity, not symptom burden.

Fatigue can be driven by disrupted sleep, nerve sensitivity, stress responses, or the cumulative load of managing symptoms. It does not always track inflammation.

Yes. Over half of people in the IBD-BOOST survey reported bowel incontinence in the previous week, even outside acute flares.

Not always. Pain can persist due to nerve sensitisation or functional changes, even when tests suggest remission.

Some people benefit, especially with good engagement. Large trials show mixed results overall, which points to the need for better-fitting support rather than lack of effort.

Sources and further reading

- IBD-BOOST Programme lay summary and publications

https://www.kcl.ac.uk/research/ibd-boost - Norton et al. Living well with Crohn’s and Colitis fatigue, pain and urgency

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03570-8 - Crohn’s and Colitis UK, symptom management resources

https://crohnsandcolitis.org.uk